I wasn’t fully aware of the magnitude of India's unemployment problem. While we all had some idea, I never really delved into the numbers to grasp the full extent of it. It’s even more fascinating to consider its repercussions from both a business and investing perspective, as well as its impact on the current political landscape.

Let’s start with where it all began:

Fertility rate—

our grandparents likely had at least six children or more, and depending on your age, your parents probably had around four to five children. At that time (much like today), India was in a very poor state, growing at what was often referred to as the "Hindu rate of growth"—a mere 3%—due to the socialist policies of the government. As we’ve all seen or experienced in our lives, being poor and having many children creates an even bigger challenge to escape poverty. More children in the family place additional constraints on resources until they become productive, but due to the lack of resources, educating them wasn’t always possible. This creates an even bigger strain when they grow up and are forced to take low-skill jobs, if they can find one. This is where the lack of jobs creates immense pressure on the lives of billions of people today.

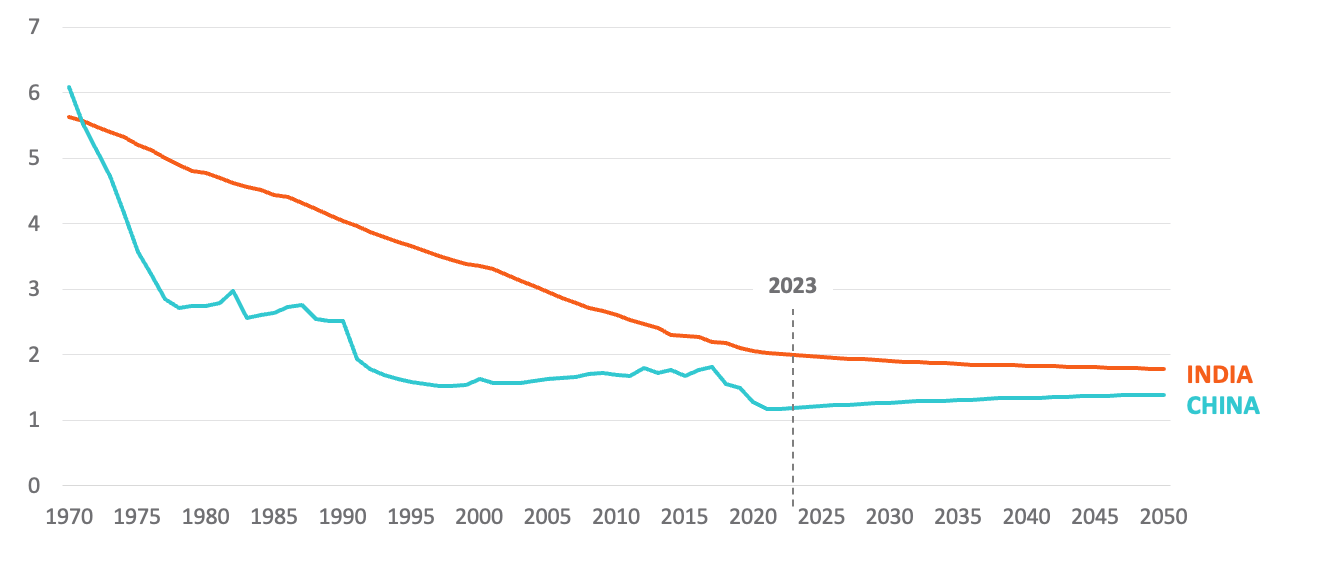

Just as having more children can be a bad idea for a poor family, having a high fertility rate in India during the 1950s to 1970s was perhaps not the best strategy for a nation struggling with poverty. The Chinese recognized this issue early on and successfully brought their fertility rate below 2 by the 1990s, a level that India has only achieved today.

Due to high fertility rate back then today In India, approximately 6.5 million (65 lacs) graduates complete their degrees annually. This figure includes around 1.5 million (15 lacs) engineers, with the remainder consisting of graduates from various other disciplines such as arts, commerce, and science.

The total number of graduates has shown an upward trend, with reports indicating that the number increased from 9.54 (95 lacs) million in 2020-21 to 10.7 (1.07 Cr) million in 2021-22.

We have a total of 1 crore graduates every year. The question is, how do we create 1 crore jobs annually to match this output? and we know 95% of these colleges don’t add any skill sets to the graduates.

Let’s start with engineers: out of the 15 lakh engineers who graduate each year, our massive IT industry is only able to absorb 10-15%, which translates to just 1.5 to 2 lakh engineers annually and because of this massive supply The average annual salary for IT freshers in India is approximately ₹2.3 Lakhs from last 20 years (isn’t this crazy ?).

The average salary of truck drives hadn’t change in last 10 years which is about 25-30 thousand per month.

The average salary of delivery boys hasn’t changed in the last 10 years, remaining around ₹2.5 lakhs per year, which is also approximately the average salary of a graduate engineer. This is one of the reasons why quick commerce and food delivery have been such massive successes in India—labor costs aren’t rising due to this vast supply of cheap labor. Similarly, this is also why the IT industry has flourished in India.

Quick commerce failed in many developed nations but its next big thing in India due to again lack of proper employment in India for 1 crore graduating youths every year.

Isn’t food or grocery delivery considered employment? I would argue no, because the salary is likely to remain the same even after 20 years. At least in IT, your experience counts and your salary grows over time. In delivery jobs, however, your experience holds no value at all as many no skilled youth coming out of college ready to take your job.

Reports indicate that over 40% of graduates under 25 struggle to find any employment (even delivery kind of jobs).

How India can absorb 40 lac more graduates every year ? For this we have to grow at 15%.

It all started because we had a high fertility rate during the 1950s to 1970s, but low economic growth rates, leaving the economy unprepared to employ the large number of youths graduating 20 to 30 years later.

We've touched a bit on the business impact of this: the cost pressures from delivery boys will remain minimal, and the salaries of IT freshers are unlikely to change significantly over the next 20 years also.

The reason we can’t create enough jobs is that in our service-based economy, the 8-10 crore high- to middle-income group is being served by the rest of the 100 crore low-income group, while another 20-30 crore farmers are feeding the entire population. The problem is that the consumption class is too small, and the serving class is too large.

And this imbalance has its own political repercussions:

a) Higher taxes on the middle class can always be justified, as the government has few other avenues for collecting revenue.

b) The massive unemployed class, which has been growing by 40 lakh per year for a long time, needs government support in the form of freebies.

c) This large serving class of around 100 crore people will continuously demand more reservations in government jobs and more populist schemes, as the country is not creating enough opportunities for them.

Can creating massive low skill manufacturing solve it ?

China

China had around 109 million (10.9 Cr) manufacturing employees as of 2002. This number has likely grown significantly since then as China's manufacturing sector expanded.

In 2022, employment in industry (which includes manufacturing) accounted for 32.15% of China's total employment.

China's manufacturing sector has shed surplus workers from inefficient state-owned factories while increasing employment in the private sector. (PSU to PVT Job migration Can you imagine this happening India ?)

On the other hand India produces around 29 lakh per annum between 2013 and 2019.

Manufacturing can solve it but we haven’t cracked it yet despite governments efforts.

Its a very hard problem to solve for the government but the political implication of it is social unrest or more populist governments coming to power.

I’m unsure whether having an massive unemployable youth population is a demographic dividend or a demographic disaster—only time will tell.

The only silver lining is that India's fertility rate has now fallen below 2, and if we continue to grow at 7-8% for the next 20 years, the number of youths entering the job market will significantly decrease. This reduction in supply could help bring down the unemployment rate substantially over a long run. Perhaps freshers salary probably will start increase then in IT sector, provided we don’t have a populist government in between screwing up everything.